Red Foliage | Parthenón-fríz Hall, Budapest | 2023

16 – 26 May 2023

In his latest solo exhibition, Zsolt Molnár continues his previous practice of exploring the internal mechanisms of living organisms and ecosystems. His 2023 series, which can now be seen for the first time, is an organic continuation of the works presented in his solo exhibition Along the Edge of the Leaf (2021), and a further reflection of the problems and themes dealt with there, unfolded in new and more complex formal solutions.

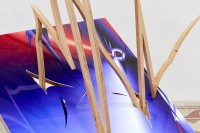

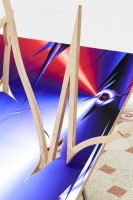

The works focus on vocabulary and concepts such as attack, defence (attack as defence), vulnerability: the coexistence of flora and fauna that sometimes seems almost like a continuous war, the aggressiveness of self-defence – the dual nature of the struggle for survival. In this stage of his creative method, which is typical of the artist in that it collides/reconciles two and three dimensions and displays tensions and tipping points of equilibrium, the two-dimensional graphic’s occupation of space, its expansion beyond its own limits, the interpenetration of the two into each other’s space, plays an even more prominent role than before. The forms (such as the caterpillar’s chewing leaves, spines, tentacles, chewing organs), which are related to the phenomena the artist is investigating more closely and are abstracted almost beyond recognition, but which emphasise their essence through this very fact, now include the human figure.

Eszter Márkus

***

Zsolt Molnár is an astronaut. He takes the flora with him on his rocket, and unintentionally, one also has to observe the fauna that accompanies the vegetation. The lights come from the unmoved, all-pervasive light sources of space, unfiltered by clouds and vapour, with a metallic glow, making the phenomena precisely visible. It is necessary to think about how to maintain a balance between pests and crops in the conquered territory, from the human point of view. He is not only an astronaut but also a colonist, thus lacking the romantic attitude of the city dweller when looking at nature. His relationship with the environment is affectionate but not sentimental. He does not shed tears at the sight of a pile of mess, weeds and invasive vines, to see how beautiful it is, but he tears it apart, interprets it, cultivates it, pushes it back. As usual with art, once again we are witnessing the construction of a Universe maquette. The biomorphic and the technical are both present, all of it permeated by speed. We do not see fixed, static situations, but situations of momentary equilibrium in progress. Sci-fi, in short. Disciplined momentum, controlled growth, no room for imprecision. Looking for what can spread out and away, which force will be the determining one. Its precision is not merely the accuracy of the box cutter (that can be wielded), but of the endeavour. Momentum, aspiration are all vectors, they have direction as well as velocity. The garden in which we are walking is in fact a pretext to illustrate the dynamics of larger forces, their interaction and counteraction. Whether they are marked by a steel rod, a wooden arc, or a drawing on a print, their meaning lies between their starting point and their end point, how far they run, where they run.

Let's look at the title: Red Foliage. Foliage we understand, since it is not uncommon in Zsolt's work to see palmate vine leaves and leaves as such, in general. The leaf that provides us with oxygen on earth, whose boundary, whose shape, so often captivates him. But the red! It is, after all, the opposite, the complement of the colour of the leaf (apart from the Japanese maple, which I like so much). Where can we see it here? It appears as a light that is just translucent on the crown of the leaf, the supplement. We also have a larger surface of it, looks a bit like a scaffold, it doesn’t bode well. I hate to mention wound, but these red fissures are hard to avoid that interpretation. Cutting, ripping, aggression versus defence. Also, a little dilute pink taps into the blue of space, falling in. Tentacles, gnawers, the image of a snagged tree trunk, can cross the surfaces. All these pictorial elements are supported by shiny steel legs against the supreme law of gravity, suggesting insect legs or a rocket-launching stance.

And the key to opening and closing things is a small, two-way, curved arrow that appears twice. It dialectically closes and opens, approximately in the middle of the vertically held flat graphics, in this prominent, essential area. It clearly indicates the effect and counter-effect whose balance has shaped the whole of these works.

We can also think of these works as gardens. And of gardens as structured systems, similar to language. The most important English garden designer of the 18th century, Capability Brown, comes to mind. It was his work that completed the English landscape garden. Hannah More described Brown's 'grammatical' manner in 1782: 'Now,' said Brown, pointing with his finger to a point on the estate below, 'there I put a comma, and there,' he pointed to another place, 'where there is a more definite turn, I put a colon correctly; at another part, where a pause is wanted to break the view, a parenthesis; now a full stop, and then I begin on another subject.' Thus, he edited his gardens, forming sentences and statements, many of which we can still admire today. This way of thinking reminds me of Zsolt Molnár's work. 'Now, ' says Zsolt, I think, 'I put a comma there, and there, ' he points to another place, 'where there is a more definite turn of phrase, I put a colon; in another place, where a pause is desirable to break the view, a parenthesis; now a full stop, and then I move on to another subject.'

Katalin Káldi